Before establishing Degmo, its director, Hamish Wilson, had for many years lived in Africa amongst Somali nomads as well as collaborating with Somali communities in the UK to promote wider understanding of their culture and history. He was thus well aware of the importance Somalis attach to impressing upon each new generation the values of the pastoral tradition which has for centuries shaped Somali society. Hamish was also mindful of concerns being expressed by increasing numbers of older Somalis and community leaders of all ages about the adverse effects on their children of growing up isolated from the influences of traditional rural life and the wealth of culture it contains. Of equal concern was the demoralising effect of sustained exposure to media reports portraying the Somali people as a failed society. Ignorant of the many positive aspects to their history, stigmatised by those around them, it had become common to find Somali youths keen to disown their own Somali identity. Loss of identity, especially amongst young male Somalis, concluded the elders and leaders, was exasperating a sense of alienation and contributing to lack of achievement at school and, in extreme cases, leading to a life of disillusionment and crime.

So when the opportunity arose for Hamish and his family to acquire the farm at Hangingheld, so too was born the idea that the Somali tradition of sending families to the countryside to reconnect with their rural roots might be recreated in the UK. Could visits to the farm featuring the history and culture of rural life in both Britain and Somalia not only assist older Somalis to integrate more fully into their adopted country, but also inspire younger generations to be proud of their Somali identity? Every Somali to whom Hamish spoke believed it could. The result was Degmo.

Who we are

Hamish Wilson, together with his wife, Nell, and two young sons, Forbes and Angus, hosts all visits to their farm. In the planning and management of Degmo they are assisted and advised by a board of Somali patrons. Further guidance is provided by partnerships with Somali community groups from around the UK as well as Somali specialists working in the fields of education, mental health and the probation services.

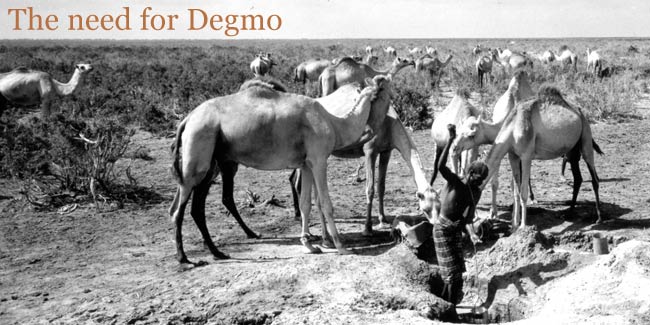

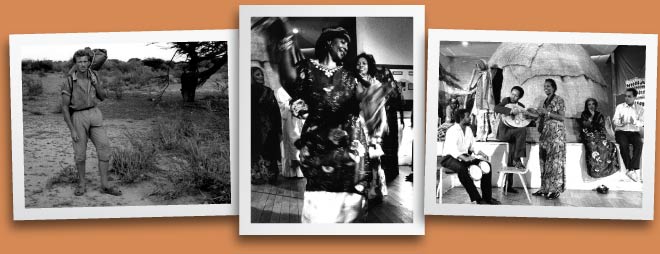

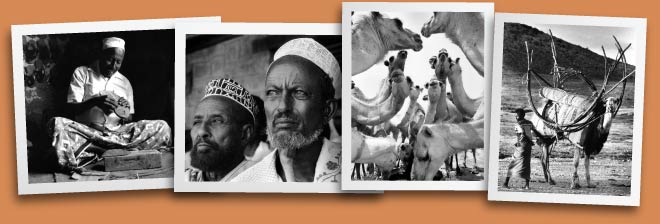

In addition to farming, Hamish is a photographer, writer, lecturer and broadcaster who specialises in Somali culture and affairs. He is also an accomplished camel boy who, over the course of the past twenty-five years, has lived and travelled extensively amongst the nomads of the Somali region.

During this time Hamish has had his photographs of the Somali region reproduced in national and international publications and exhibited in galleries and museums around the UK and Scandinavia. He has worked as a freelance correspondent for the BBC World Service, written for the Sunday Times newspaper, and contributed to several specialist African publications. In 2000 Hamish wrote and presented "The Forbidden Journey", a T.V. documentary for BBC 2, and has acted as a consultant to ITN news and BBC T.V. factual programming.

Hamish has conducted research in Somalia on behalf of the human rights group "African Rights" and been employed as a specialist regional advisor on the Somali region by security consultancy groups. He has also worked with the government of the Republic of Somaliland and United Nations on disarmament, demobilisation, and de-mining programmes in the region.

In collaboration with Somali communities, Hamish provides consultancies to education and social services departments in Bristol, East London, Sheffield, Manchester, Liverpool, Cardiff, Newport and Milton Keynes and has been employed by police forces to advise on community relations issues and traditional Somali law. He lecturers to schools, universities, and institutions including the Royal Geographical Society.

A Somali legacy - How a bond between two families lead to the creation of Degmo.

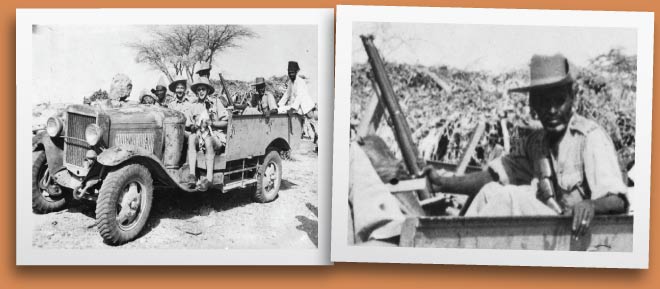

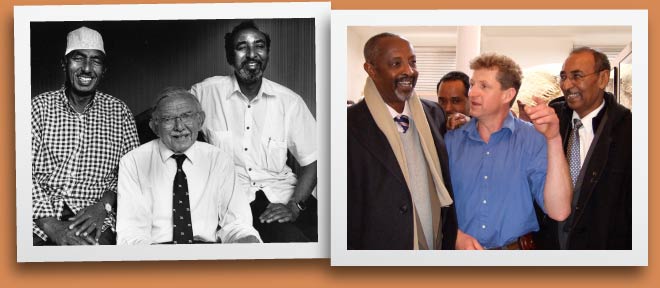

Hamish's involvement with the Somali people is a legacy of his father's friendship with a remarkable Somali named Omar Kujoog. It was whilst serving and travelling in British Somaliland in the 1930's that Eric Wilson met and became friends with Omar Kujoog. However, in August of 1940, when the two men stood side by side as soldiers in the Somaliland Camel Corps defending a hillside against an invading Italian Army, the friendship was tragically cut short. At the end of the first day of fighting, Omar Kujoog was struck and killed instantly by an enemy shell which also severely wounded Hamish's father.

The battle raged for a further four days during which Eric Wilson clung to his machine-gun position and, as well as contracting malaria, was wounded several times more. When he and his men were eventually overrun, the advancing Italians reported all occupants of the position killed in action. For his bravery Eric Wilson was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross and his obituary published in the British newspapers. But he was not dead. The day after the battle had ended, whilst searching in vain for the vanished British forces, he had been captured by another division of Italian soldiers and imprisoned in a prisoner of war camp deep inside Ethiopia.

Whilst held prisoner Eric Wilson received news of his award of the V.C. from a recent arrival at the camp, but refused to believe it. After seven months of imprisonment, and on the eve of his escape via a tunnel he and his fellow prisoners had dug, the camp was captured by returning British forces. To his astonishment, Eric Wilson received confirmation of his award from the officer leading the force. However, he remained uncomfortable at having been singled out for praise and up until his death at the age of 96 on the 23rd of December 2008, Hamish's father maintained his insistence that the V.C. awarded him be regarded as an honour he shared with Omar Kujoog and the other Somalis alongside whom he had fought.

For the remainder of the war and during the years which followed, Eric Wilson served, worked and lived alongside not only other Somalis, but people from all over Africa, however he never succeeded in making contact with the families of those who had died beside him in 1940. Some years later, and now back in Britain, Eric Wilson received a telephone call from a mysterious stranger who enquired as to whether he could recall a man named Omar Kujoog. "Why of course," he replied, "I still carry embedded in my flesh the remains of the shell that killed him!" "I am Husseen" said the man on the telephone, "The eldest son of Omar Kujoog."

The next day Husseen arrived from London at the Wilson family home in Somerset and in so doing re-kindled a friendship between the two families which has endured to this day, now spanning four generations of Kujoogs and three of Wilsons.

Degmo is the continuation of this bond between the two families and indeed, without a remarkable sacrifice from Hamish's father, Degmo could never have happened. When the chance for Hamish to purchase Hangingheld Farm arose and with it, create Degmo, he and his family were unable to raise the necessary funds. Seeing how great was the opportunity to help both his family and the Somali community, Eric Wilson sold his Victoria Cross and put the proceeds towards the cost of the farm, thus making it possible for Hamish to secure a loan for the remaining sum of money.

Fortunately Eric Wilson lived long enough to see the formation of Degmo and by the time of his death be satisfied that the legacy of his friendship with Omaar Kujoog would survive for many generations to come.